Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are more effective than antibacterial soaps but don’t give up on plain soap and water.

That our hands are crawling with germs is old, old news. Adults have hectored children about the dangers of unwashed hands for generations. Over a century ago, a few pioneering doctors (Holmes, Semmelweis, Lister) figured out that physicians’ hands were infecting patients and making many people sick.

What is new, though, is the range of organisms you might find on even a seemingly clean pair of hands.

It’s pretty normal to have staph germs living on your skin (and in your nose): About 25%–30% of us are “colonized” with no ill effects — unless the bacteria get into a break in the skin. But a new version is increasingly prevalent: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacterium that resists not only methicillin but many other antibiotics. MRSA was once almost exclusively found in hospitals. Now outbreaks are occurring at schools, in jails, and among sports teams. Members of the Boston Celtics pro basketball team were infected in the fall of 2006

Clostridium difficile, a bacterium found in feces, is another hospital germ that’s flown the health care coop. Hands are often the middleman in the fecal-oral transmission route: C. difficile gets on people’s hands when they come in contact with a contaminated surface or object, and they inadvertently infect themselves when their hands touch their mouth.

Our hands are much more hospitable to bacteria than to viruses, but you’ll find a few of the latter. Most flu is transmitted through the air in virus-laden droplets propelled by coughs and sneezes. But our hands can pick up those droplets from any number of surfaces, so they’re often an important link in the chain of transmission. Hand washing is a standard item on flu-prevention lists, and health officials are putting special emphasis on it now because of the bird flu epidemic.

Americans say they wash their hands. Over 90% of those questioned in a telephone survey said they washed up after using a public bathroom. But when the American Society of Microbiology and a trade association group observed people in public restrooms (in stadiums, train stations, etc.), they found that only 75% of men washed their hands. Women weren’t perfect, but at 90%, they did better than the men. This Mars-Venus disparity extends to those with medical degrees. In one study, female physicians washed their hands 88% of the time after seeing a patient; their male colleagues did so only 54% of the time.

Overkill overdoes it

There are those, both men and women, who overdo the hand washing. Our hands weren’t meant to be sterile objects. Having some bacteria on the skin is perfectly natural, and “resident flora,” as the experts call it, is probably healthful — unless you’re a surgeon about to put your hands inside someone’s body. Frequent hand washing, even with mild soap, can damage skin, worsening cuts and causing cracks that can harbor even more bacteria. Dry, damaged skin may also spread germs more easily because it flakes off, taking bacteria with it.

How often should you wash your hands? There’s no set frequency; it really depends on your activities. Must-wash occasions include after using the bathroom, before eating or preparing food, and after being with someone who’s ill, particularly if he or she has a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection.

Lathering up

New products clamor for our attention, but plain old soap and water is still a good way to clean your hands. In studies, washing hands with soap and water for 15 seconds (about the time it takes to sing one chorus of “Happy Birthday to You”) reduces bacterial counts by about 90%. When another 15 seconds is added, bacterial counts drop by close to 99.9% (bacterial counts are measured in logarithmic reductions). Few of us wash our hands that long — 5 seconds is more like it. One reason you’re supposed to use cool or lukewarm water is to increase the chances you’ll wash them a little longer. Hot water is also more damaging to the skin.

Soap and water don’t kill germs; they work by mechanically removing them from your hands. Running water by itself does a pretty good job of germ removal, but soap increases the overall effectiveness by pulling unwanted material off the skin and into the water. In fact, if your hands are visibly dirty or have food on them, soap and water are more effective than the alcohol-based “hand sanitizers” because the proteins and fats in food tend to reduce alcohol’s germ-killing power. This is one of the main reasons soap and water are still favored in the food industry.

Even people who are conscientious about washing their hands make the mistake of not drying them properly. Wet hands are more likely to spread germs than dry ones. It takes about 20 seconds to dry your hands well if you’re using paper or cloth towels and 30–45 seconds under an air dryer.

Antibacterial soap

By some accounts, almost half of the hand soaps on the market have an antibacterial additive. Many brands are in liquid form, so they’re less messy than a traditional bar of soap, but you can, of course, buy plain soap in liquid form, too.

The active ingredient in most antibacterial soaps is a chemical called triclosan. Triclosan in the amounts used in soap doesn’t kill many bacteria (concentrations of 0.2% or less), but it keeps the counts down partly because it has residual activity.

The big question has been whether widespread use of antibacterial soaps will worsen the problem of antibiotic resistance. Doctors have worried that bacteria exposed to low levels of triclosan aren’t killed outright so much as given an opportunity to mutate so their offspring are more resistant to triclosan and, ultimately, to antibiotics as well. In the lab, that’s how it has played out: Bacteria that become less susceptible to triclosan show indications of developing “cross-resistance” to antibiotics.

But what happens outside the lab is less clear. In the biggest study of its kind, researchers recruited about 240 households in upper Manhattan to participate in a “real-world” handwashing study. Half were randomized to use 0.2% triclosan soap; half, to plain soap. After a year, the researchers tested the hands of the primary caregivers in the households for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The result: no statistically significant difference between antibacterial and plain-soap households. The researchers offered several possible explanations for their findings (resistance may not develop in a year; high antibiotic use may make it difficult to detect small changes), so the case isn’t closed, but their findings do counter the lab research.

Even if antibiotic resistance weren’t an issue, results from this study (and others) make you wonder if the antibacterial soaps available to consumers add much to hand hygiene. In the Manhattan households, a year of washing with an antibacterial soap didn’t lower bacterial counts on hands any more than a year of washing with plain soap. Nor did the antibacterial soap households experience fewer cold-like symptoms. That’s not surprising: Colds are caused by viruses, not bacteria. Still, the finding is a useful reminder that the antibacterial soaps aren’t the all-purpose germ fighters that many people expect them to be.

- Don’t scrub. Scrubbing can damage skin, especially if you do it a lot. The resulting cracks and small cuts give pathogens a place to grow.

- Keep your fingernails short. Bacteria like the area under our fingernails. Long nails make it more difficult to keep those areas clean.

- Use hand lotions, especially during the winter. Keeping the skin of your hands intact is essential to good hand hygiene.

- Don’t be in such a hurry. It takes about a minute to properly wash and dry your hands.

Rubbing it in

The hot new products in hand hygiene are alcohol-based rubs, sold as “hand sanitizers.” Purell is the most popular brand-name product, but you’ll pay considerably less if you buy a store-brand version. The big advantage of the alcohol-based cleaners is that you don’t need water (you just rub the stuff on your hands) or a towel, so they can be used anywhere, not just in the bathroom. Politicians use them on the campaign trail (see box), and we’ve spotted bottles on people’s desks and in their cars. Although many surgeons still scrub in the way seen on television, some have switched to an alcohol-based foam, transforming that iconic image of hand hygiene.

In his book, Sen. Barack Obama says President Bush is an enthusiastic user of hand sanitizers. Obama describes a brief conversation he had with the president during a visit to the White House. “Good stuff keeps you from getting colds,” Bush told the Illinois senator before offering him a squirt, which the Democrat says he accepted because he “did not want to appear unhygienic.”

Perhaps this is one area of bipartisan agreement. According to The New York Times, Obama now keeps his own bottle of an alcohol-based cleanser in his travel bag.

Alcohol’s killing power comes from its ability to change the shape of (denature) proteins crucial to the survival of bacteria and viruses. In the United States, most of the alcohol-based hand cleansers sold to consumers are 62% alcohol. By itself, alcohol would completely dry out people’s hands, so various skin conditioners are added. Alcohol does a superb job of getting rid of bacteria and even some viruses. In all but a few trials, alcohol-based cleaners have reduced bacterial counts on hands better than plain soap, several kinds of antibacterial soap, and even iodine.

But alcohol doesn’t kill everything: bacterial spores, some protozoa, and certain “nonenveloped” viruses aren’t affected. That’s why it shouldn’t be the only cleaner available in hospitals or other health care settings, according to Dr. Duncan Macdonald, a surgeon in Glasgow, Scotland, who has studied hand hygiene. Dr. Macdonald says hospitals where he has worked go back to soap and water during “winter vomiting outbreaks” caused by nonenveloped viruses.

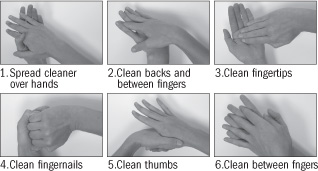

To be effective, the alcohol-based rubs need to come into contact with all the surfaces of your hands — back, front, in between the fingers, and so forth. For that reason, studies have shown that using small amounts — 0.2 milliliters (ml) to 0.5 ml — is really no better than washing with plain soap and water. Dr. Macdonald reported study results in 2005 that showed coverage with an alcohol-based gel improved considerably when he had hospital staff members double the amount they used from 1.75 ml to 3.5 ml. In another study, Dr. Macdonald found that coverage also improved if staff members saw the areas they missed under ultraviolet light and were then shown the six handwashing steps designed to maximize coverage, regardless of the type of cleanser (see illustration).

At the Health Letter, when we measured a squirt from a bottle of Purell hand sanitizer, it was 0.5 ml at most, which would suggest that a single squirt isn’t much better than washing hands the old-fashioned way. So keep in mind that the way we actually use alcohol-based products may not be leaving our hands quite as germ-free as we suppose. On the other hand (pun intended), their convenience may mean people will clean their hands more often, especially if they’re on the go, so hand hygiene might improve overall.

Dr. Macdonald sees no need to use alcohol rubs at home: “I use regular soap and hot water and have no intention of throwing out my pleasant-smelling lotions for alcohol rubs. Most of the germs around the home have come from us and live with us in perfect harmony.” The exception, he adds, might be if you are caring for someone who’s at high risk for infection.

Source: https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/The_handiwork_of_good_health